“I allocate, therefore I am.” These words were uttered with gloomy resignation by a beleaguered risk manager. The lack of enthusiasm is understandable; it is hard to get jazzed about a process whose best result is often described as “making sure everybody is only a little unhappy”.

When a firm buys insurance via a centralized risk management function, it hopes to enjoy the economies of scale of the unified consolidated organisation. In fact, many captive insurers are used to facilitate an “internal risk pooling” function, in which the consolidated group accepts a larger firmwide risk retention, the business units take smaller individual retentions, and the captive insures the gap between the two.

Using the captive allows the organisation to harness the economic strength, size, and risk-taking ability of the larger combined group, while recognising the smaller risk appetites of the component business units.

Alternatively, the business units may be buying “ground-up” coverage from the captive, while paying an allocated share of the firmwide premiums and retained losses.

Actuarial consultants are often enlisted to model the risks and develop loss projections and even “premiums” within the risk retention layer, considering the many factors typically considered in an underwriting process: exposure, loss history, volatility, and other factors. Brokers may be enlisted as well, providing market indications for captive “infill” policies.

The benefits of centralized risk management can only be realized, however, when the firm-wide insurance premiums are allocated in a fair, equitable manner among the different component entities of that firm.

The allocation framework must address the needs of multiple stakeholders, including business unit managers, financial reporting and tax professionals, and individuals tasked with government contracting – as well as corporate risk management itself.

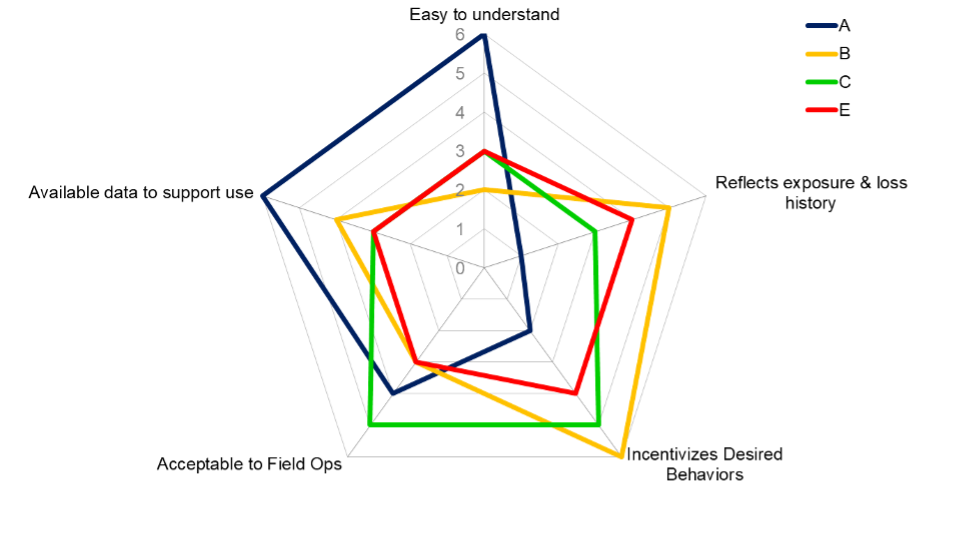

And the complexity builds. Allocation frameworks have multiple goals: all of them worthy, and many of them in conflict with one another. Think about this set of goals for an allocation system:

Considers loss history: Business units with favorable past experience should be rewarded, and those with poor experience should be surcharged.

Considers Exposure to loss: Business units need to be compared based on the relative “size” of their risks. While this is often measured in simple terms such as payroll, vehicle counts, sales or square footage, it is also often a complex question that must also consider underlying “riskiness” of the businesses, geography, or other considerations, especially with highly diversified firms.

Incentivizes Desired Behaviors: Business units that adhere closely to safety and loss prevention protocols should be rewarded, and those who lag behind should suffer negative consequences. Other compliance areas to focus on include claims reporting deadlines and return to work practices.

Should produce better-than-market results: Business units should not be able to approach the insurance market on a stand-alone basis and improve on their allocated share of the firmwide policy. This issue frequently arises with international operations and can prove challenging in diversified conglomerates where one subsidiary drives up the cost for the entire firm, or where one subsidiary is a stand-out performer in a group of otherwise average performers.

Supportable and repeatable: There needs to be sufficient reliable data to support the allocation approach, making similar calculations over multiple periods. Having a consistent approach to cost allocations from year to year also establishes credibility with government contract auditors who may be enforcing Cost Accounting Standards, as well as tax auditors.

Transparent and easy-to-understand: Stakeholders need to be able to comprehend the methodology used in the allocation calculations.

It is difficult if not impossible to create an approach that fully satisfies all the objectives. Above all, the allocation approach must be perceived as “fair,” so that each entity receives equal and non-preferential treatment.

This is important not only in preserving internal relationships and cooperation, but in satisfying the needs of external parties such as public entities, who may be paying “pass-through” insurance allocations as part of a contractual agreement.

Premiums invoiced by related-party captives often attract extra attention, and these parties will need to be satisfied that subsidiaries are not subsidizing one another at the government’s expense, and that premiums were developed using reasonable, actuarially sound methodologies.

There are numerous available tools for solving this riddle. One can create, with relative ease, an allocation spreadsheet that meets one or several of these objectives using relative weightings of exposure and/or loss experience, and some long division.

But this leaves behind some nuanced approaches that introduce real-world considerations such as minimum and maximum premiums, budgetary constraints of the subsidiaries, uneven and varying need for excess policy limits, acquisitions and divestitures, and new emerging classes of risk in which the firm has no meaningful track record.

One actuary suggested a capital allocation model that blends both average and marginal cost of risk capital for all subsidiaries into a single premium and risk allocation formula. Analysis for an organisation with ten business units would start with a single operation and then review the marginal risk created by including each additional business unit until all ten have been included – in every possible permutation.

This results in over 3.6 million possible combinations – well beyond the capability of a spreadsheet program – but it also goes a long way to ensure that risks are allocated even-handedly. At this point, we have departed simple arithmetic and entered statistical modeling.

Nearly all risk managers interviewed on the subject agree on this: getting allocation right is a multi-year learning process that requires patience, consensus, feedback, adjustment and revision.

All agreed on the adage, “what gets measured gets done”. That is, individuals and even organisations will manage their activities to achieve the measurable targets that have been set for them, often with unintended consequences. Here are a few stories, and the lessons learned:

One risk manager interested in creating a reward and chargeback system based on loss experience realised that while the business unit had some ability to prevent workplace accidents, it had little or no ability to control the cost of those accidents once they occurred.

Basing an allocation on the total cost of claims seemed punitive, because the local management did not control claims once they occurred. As a result, the allocation system was modified to measure claim counts, rather than the total cost of claims.

Another risk manager, who was initially satisfied at creating an allocation and chargeback system that measured exposures, loss history, adherence to risk management protocols and return-to-work goals, eventually realized that the system was so complex and opaque that local managers did not feel they could control their outcomes. The calculations of the model needed to be simplified so that all could understand how it worked – so that they could manage to the desired outcome.

In still another case, the penalties for excessive claims activity were so severe that it led the local business units to avoid or delay reporting claims. In response, the system was amended to cap chargebacks and reward prompt claims reporting.

The design process is critical, and requires careful thinking, planning and collaboration. It is essential to engage actuarial consultants and experts on government cost accounting, and it helps to seek involvement from internal parties responsible for reporting or analysing risk and loss information.

Buy-in from a wide cross-section of your organisation will improve the chances for success with the methodology selected. This includes people from accounting, legal, risk management, government contracting (as applicable) and business unit leaders.

These stakeholders should not only be involved in the development and selection of the methodology, but also in communication with the internal customers. And in that regard, support from the top levels of the organisation (e.g., Chief Financial Officer, Chief Risk Officer or even the Chief Executive Officer) will be critical.

The allocation methodology should be readily understood by the end-users: the people at the business unit who are paying the costs, and whose bottom line is directly affected by the allocation. If people cannot understand how their bill was calculated, they will be slow and resistant to accept the allocation approach. But know also that there is no single right way to allocate costs; so later, after you believe you have implemented the “perfect” methodology, be prepared to react to constructive feedback, making incremental adjustments as business conditions and objectives change.

While premium and cost allocation may appear at first glance to be a dismal topic, the benefit for the organisation is a network of incentives and rewards that move the company closer to its business and risk management objectives. It is important to invest the appropriate time and involve the right stakeholders and experts at the outset.

And if you’re finding that the onus of performing allocations drives you to use existential language, remember that you do have the available tools to make this process be all that it can be.